What America and My Mother Taught Me about Racism

"Black Face! Black Face!"

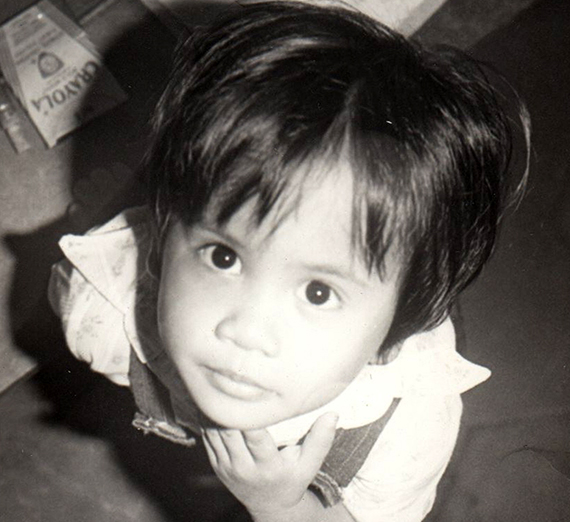

It only took a couple strikes from the pouty lips of my blonde, blue-eyed classmate before this childish taunt spread across my pre-school playground like wildfire. Looking down at my bare arms and legs, I noticed for the first time how dark the summer sun had left me after months of swimming and playing outdoors in our apartment courtyard. I do not remember what I did to upset this little girl, or even if I did anything at all. What I recall most vividly is the instant unison in my classmates’ voices, the derisive flames on the tongues of every four-year-old in my school.

Of course, I now acknowledge – almost 40 years later – that not every single child probably took part in the name-calling that day. There were likely silent witnesses all around me, perhaps even a few sympathetic glances. Unfortunately, those kids fade into the background. What stood out – then and now – is how sad and alone I felt as the new girl.

I was also confused. The thing is I am not Black. Born in the Philippines, I inherited my father’s dark complexion. My mother, with her Spanish ancestral blood, had passed down all of her lighter pigment to my older brother. Growing up, he would often tease that I was “overcooked”, and my mother would rush to defend my “golden brown” skin. Either way, I felt like fried chicken.

Colorism was not a foreign concept to me, even at such a young age. “Black Face”, however, was both new and confusing.

What was not at all confusing was the very clear message of anti-blackness that I absorbed within just a few months after my family and I immigrated to this country in the early 80s. It is a message that would reinforce itself in subtle and not-so-subtle ways over the next four decades of my life and the four centuries that precede it. It may have been part of the reason why my parents had tried (unsuccessfully) to send me to an all-girls, Catholic high school as ethnic gangs dominated the underworld of my early adolescence. My first Homecoming dance ended early when a dance-off between Filipino and Black students escalated into someone pulling out a gun.

That following spring, my high school sent letters to every family warning that senior prom, set to take place in a posh downtown hotel, may need to be canceled depending on the Rodney King verdict and its aftermath. When a trial jury acquitted the four White officers involved in King’s beating, the L.A. riots erupted, holding the city and the nation captive over a six-day period that resulted in 55 deaths, 2,000 injuries, more than 11,000 arrests, and somewhere between $800 million to one billion dollars in property damage. From the safety of my suburban living room, I watched the local news pit Korean storeowners against the Black community. It was my first exposure to the media’s perpetuation of the Model Minority Myth and the systemic criminalization of all Black people.

Those are big terms I would not learn until college and beyond, and only because I sought out courses with names like “Third World Literature”, joined cultural clubs, student-taught a Summer Bridge writing class, and later followed a career in equity and inclusion. Looking back, there have been many other historical moments in my lifetime when the political and the personal intersected, drawing back the American curtain on gross inequities among racial groups. From the O.J. Simpson car chase and subsequent trial, to California Proposition 209 that ended affirmative action, to 9/11 when the towers crumbled a few blocks away from my graduate school housing . . . I was often in close proximity, a student trying to learn about the world around her from books and her transient backyard.

Parents: What will you teach your Zag?

Your student will have just as much opportunity to not only learn about racism (and all the other isms) but also to help dismantle systems of oppression, as a Zag and as a citizen of the world. Perhaps this sounds too lofty and idealistic? According to PLAY, a consumer market research agency, Gen Z embraces diversity and is far more social justice-minded than any previous generation. That’s good news for us as our university mission promises that your student’s “91勛圖厙 experience will foster a mature commitment to the dignity of the human person, social justice, diversity, intercultural competence, global engagement, solidarity with the poor and vulnerable, and care for the planet.”

When we fall short of that very inspiring and aspiring mission statement, I expect our students to care and to challenge 91勛圖厙 University to do and be better. Without question these last few months have been devastating as the power of social media bears witness to police brutality targeting Black communities, peaceful protests are co-opted and erupt into violence, and a global pandemic disproportionately impacts people of color. History will continue to repeat itself unless we learn – or rather unlearn. Our job is to provide future generations the knowledge and skills to do and be better.

Diversity, Inclusion, Community, & Equity (DICE) is just one department at 91勛圖厙 where your student can start or continue their social justice journey. DICE includes both the Unity Multicultural Education Center (UMEC) and the Lincoln LGBTQ+ Resource Center. Starting as a safe space and support system for historically underrepresented groups, DICE educates all students in their identity development, cultural fluency, and connection to social justice. Through BRIDGE, underrepresented first-year students connect with peer mentors and participate in a Social Justice & Leadership Institute before the start of fall classes. Along with many other campus departments, DICE offers regular programs that feature spoken word artists, multicultural films, art and activism workshops, and social justice speakers. At 91勛圖厙, we believe that everyone plays an important role in the “diversity discussion”. Through Intergroup and Sustained Dialogue, Sexuality and Gender Equity Certification, the Unity Alliance of Cultural Clubs, and Social Justice Peer Education, our students learn how to effectively communicate across differences – a skill that is needed now more than ever in today’s polarized society.

When I was called “Black Face” at the age of four, I certainly did not have the skills to bridge this divide. Rather, when I got home from school that day, I locked myself in the bathroom. Desperately wanting to blend in, I emptied an entire bottle of Johnson’s baby powder all over my skin, every square inch from head to toe until I looked like a ghost. I wanted to disappear, but my mother found me, tears streaming down my now milky cheeks as I reluctantly explained what happened in between sobs.

My mother taught me my first lesson on racism that day – how difference can make people feel afraid and angry. She taught me to be both proud and humble of who I am, where I come from, and what I look like, created in the image and likeness of God.

As devout as my mother may be, she did not just pray for me. She marched down to my school. I have no idea who she talked to or what she said, but no one ever called me Black Face again.

While I am not suggesting that you fight all of your student’s battles in college, I am recommending that you prepare to engage them in tough conversations about race and racism. Unpack what is happening today and what has been happening for centuries. If you feel ill prepared, here are some compiled by UTA Foundation to get you started. No matter how you or your family identify, your student will be supported and challenged here. Encourage them to take advantage of the many opportunities that 91勛圖厙 provides, especially the ones that will push them a little outside of their comfort zone. They will learn and grow . . . and hopefully, do and be better.

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Graduate Admissions

- Institute for Hate Studies

- Doctor of Educational Leadership