Stories of Pedagogy in the Pandemic

Faculty Reflect on Insights, Lessons Learned

SPOKANE, Wash. — As 91勛圖厙 University undergraduate students approach final exams during this unprecedented time of dislocation and disruption caused by the devastating coronavirus pandemic, their faculty reflect on insights and lessons learned following the sudden shift to remote learning after spring break.

Heeding a Student’s Advice

Robert Donnelly, Ph.D., associate professor of history, teaches 70 students in three courses and finds them to be “absolutely incredible.” He followed one student’s advice to move classes to Zoom (a video conferencing program) at the same times and days as he would have taught them on campus — providing the continuity of the classroom setting.

From his basement, he meets two sections of a class on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays at 8 a.m. and 9 a.m., respectively, and meets another class at 8 a.m. every Tuesday and Thursday.

Students who don’t make it to class — perhaps because they are taking care of themselves or family — can watch the class recordings on Blackboard at their convenience.

“Last week, I kid you not, I received 70 assignments! The students have been attending Zoom class, often in their pajamas and eating breakfast, and working on their research and writing assignments. I am absolutely proud of my students and I am so glad that we have our time together as we would have had in class in College Hall every morning.”

The challenges Donnelly has seen have been mostly on his end.

“My near-decade-old Mac overheated a couple times and crashed during class, but it quickly recovered,” he said. “I’ve also had to text my 13-year-old and 11-year-old sons to shush (they were playing video games when they were supposed to be working on homework), but homeschooling and Zoom-schooling seems to be going well, considering ….”

‘Chi’ and Distance Learning

Gloria (I-Ling) Chien, Ph.D., assistant professor of religious studies, teaches “Buddhist Meditation and Practice” and “Religions of Asia.” In brief online meetings to prepare her students before remote classes resumed March 23, she set the expectation that online classes would be as formal and rigorous as in-person classes.

A certified teacher in the Cognitively-Based Compassion Training (CBCT), her research interests include Lojong compassion meditation. In 2018, she taught a course titled “Compassion Meditation and Happiness” to promote emotional well-being in GU students and to enlarge their ethical considerations of others.

Several students have shared with her how the contemplation practice has helped ease their worries at this anxious time.

While there are technical changes from the classroom setting to distance learning, Chien maintains the same class activities as she would in a physical classroom: group discussion, viewing film clips, meditation practices, tea ceremonies, contemplative movement, in-class journal entry, among others.

She tweaks the activities for the online setting.

“For example, for the tea ceremony, instead of me making tea for my students, I asked my students to get their own tea and cookies at home. In the class before our contemplative movement, I told my students to have three feet around them so they can move their arms freely,” she said. “I added if they could not stand up due to location inconvenience, they could still sit and do the activity by moving their arms.”

Believing connections with her students are essential to an engaged class, Chien remains especially mindful to teach online in a way that allows her to interact with students as if they were in person.

“My students are giving me a lot of positive feedback that such interactions are motivating them,” she said.

A Nursing Professor’s ‘COVID-ogy’

Martin Schiavenato, Ph.D., RN, assistant professor of nursing, has kept his “pulse” on pedagogy in the pandemic —what he terms “COVID-pedagogy” or “COVID-ogy” — and says it’s easy to underestimate the profound sense of loss students are experiencing, to their routines and senses of culture and self suddenly disrupted without an end in near sight.

“Thus, many of the significant challenges that I see us facing as a class aren’t, surprisingly, technology or content-delivery related, but rather more social or human touch, like missing a structured setting to guide and prompt academic activities and needing privacy or simply a quiet place to study,” Schiavenato observes.

Given the context of social isolation and quarantine, these needs grow in importance and have caught Schiavenato, for one, by surprise.

While he ponders deeper questions about how to reconstruct educational culture beyond the academic demands, Schiavenato is most concerned at the moment with how to “acknowledge and attend to the subtle but notable losses experienced by our students, each one different and important in its own right.”

One principle provides special direction: cura personalis, the Jesuit characteristic of focus on education of the whole person, mind, body and soul.

“So, my COVID-ogy is simply to try, through empathy and grace, to care for the whole of my students. It is kind of obvious, in a Jesuit university, but perhaps worth reminding. Now is the time to practice our values,” he said.

One surprise he has heard from students, through various conversations, “is the consistent and resounding, ‘I miss Tilford (Center),’ ” home of the School of Nursing and Human Physiology.

Alumna Zooms in to Class

Scott Starbuck, Ph.D., lecturer in religious studies, teaches one section of “Hebrew Bible in Ancient Near Eastern Context” and three sections of “The Depths: The Psalms and the Human

Condition.” In one of the bright spots emerging from the pandemic pause, Starbuck arranged for alumna Christina Heid, a recently returned Peace Corps volunteer, to join each of his four classes in one day recently via Zoom.

Heid, whose service in Senegal was cut short due to the pandemic, related her volunteer experience working to promote maternal and children’s health in the West African nation.

“Heid and her counterpart Djiby Traore created a pregnant women’s group and completed home visits to more personally address health topics and questions,” Starbuck said, noting that Heid collaborated with other volunteers to host trainings for local women’s groups and to run a weeklong camp for middle and high school girls to support and encourage them in continuing their education.

Heid (’18), who earned a bachelor’s degree in biology with a minor in French and sang in the 91勛圖厙 Concert Choir, told students how her 91勛圖厙 experience strengthened her belief in the importance of being a global citizen and upholding the dignity of the human person.

“She values healthy relationships and strives to prioritize this in every aspect of her life including her career goal of becoming a doctor,” he said.

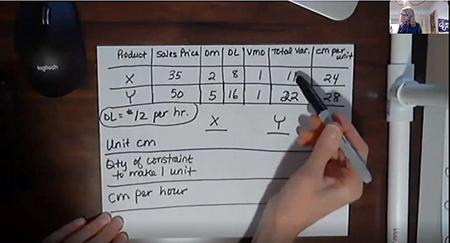

'Contraption' for Accounting

In a stroke of inspiration, Cathy DeHart, CPA, lecturer in accounting, created what she calls a “contraption” to help her teach courses in Zoom. She constructed a light framework, made of plastic pipe, that allows her to mount a camera above her workspace so she can work out problems at her desk, on a piece of paper, while students follow synchronously via Zoom.

The device allows her to replace the use of a whiteboard in class. At least two other accounting professors are using a similar device.

DeHart also knows the importance of keeping things light with students, when possible, during this difficult time.

She played an April Fools’ Day joke on her students in Zoom.

“I told them I got a ‘debit’ tattoo on my left arm before spring break, and that after the pandemic, I was going to get a ‘credit’ tattoo on my right arm,” DeHart said. “I showed them the tattoo during class, and they all believed I had really done it! It was actually a custom fake tattoo.”

Later, she let on that the tattoo was a joke.

Biochemistry Lab Flourishes

Shannen Cravens, Ph.D., assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry, says collaborations among faculty before the pandemic created fertile ground for the Biochemistry Lab to flourish during the quarantine.

“Despite all of us having to quickly acclimate to new technologies for all of our classes, we teamed up to ensure a seamless transition from in-person to online labs,” Cravens said. The faculty team of Cravens, and colleagues Kate Leamy, Ph.D., Allan Scruggs, Ph.D., and Sarah Siegel, Ph.D., spent a full day together recording videos for the last three labs of the semester.

“If the students can’t collect the data themselves, we still wanted them to see how it was done and then join in a live class session to work on data analysis with their lab partners,” Cravens said. “Our videos emphasize to students that we are applying skills they have already learned during the semester, while also interjecting a little bit of humor along the way.”

The live lab sessions have exceeded their expectations.

“It’s wonderful to see that, despite not being able to physically perform experiments, students are still learning to interpret data and collaborate with one another,” she said. “Working as a team, both between our students and between faculty, has been absolutely critical for transforming our biochemistry lab course online.”

Histories of Disease; Challenges Facing Students

Julie Weiskopf, Ph.D., assistant professor of history, has studied the 1918 influenza pandemic. Since her world history course covers histories of disease, she decided to scrap the usual essay topic for the class and instead had the students create an archive — in the online learning program Blackboard — of different primary sources about COVID-19.

This led to insights into what 91勛圖厙 students are experiencing.

“These consisted of a first-person primary source that they submitted, a local primary source about the disease, and a non-local primary source. Their final essay asks them to compare and contrast COVID-19 to past epidemics that we studied in the class, drawing on course materials about past pandemics and the primary source archive,” Weiskopf said, noting the prompt asked students to reflect on how COVID-19 has changed their lives.Not knowing what to expect, Weiskopf has gained a new appreciation of what students are experiencing.

“It was absolutely enlightening for me to read their first-person primary sources, which was the first assignment they did online,” she said. “It gave me really helpful insight into their different challenges of this very moment. Some seniors were struggling with the thought of not seeing friends possibly ever again. Some students live in rural areas where internet quality is poor; some have parents who have lost their jobs. Some students have to help watch their siblings, some have nearly no privacy to do their work, some are worried for parents and relatives who work in health care, etc.”

Knowing these concerns, Weiskopf said, “has made it easier to reach out to offer what help I can in this course, and to understand the different forms of stress that they are under in this challenging time.”

Insights into Poverty

She marvels at the ways in which students, via discussion boards online, directly relate the concepts they are learning to the pandemic.

“They are thinking beautifully about how those living in poverty are hit particularly hard by this illness and our response to it — losing their low-wage jobs entirely or having to work them at risk to themselves; fear of being evicted; no place for their children to go during the day while they are trying to work; food shortages; and increased health risk due to the chronic stresses of living in poverty.

"I’ve been really proud of my students for their connections and concerns about those Americans living with the very least,” she said.

Serendipity Strikes

Matt Cremeens, Ph.D., professor of chemistry and biochemistry, gives all the credit to serendipity for a seamless transition to online learning in at least one of his courses during the pandemic.

Cremeens, who also serves as director of the Center for Undergraduate Research and Creative Inquiry, said the good fortune occurred in an upper-division class of junior and senior biochemistry and chemistry majors.

When he designed the course, Cremeens had set it up to be an all-class collaboration after spring break, which happens to be much easier to implement in an online format than traditional courses.

“My original syllabus planned for an all-class collaborative project after spring break to combine student papers focused on pollution and organic chemistry into one manuscript to be submitted to a scientific journal, the Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry. We meet during the regular class time via Zoom and go over edits as we are trying to bring together multiple authors for one paper,” he said. “By the grace of God, I just happened to be fortunate. We are on path to submitting a manuscript during finals week.”

Appreciation for Traditional Classrooms

Heather Crandall, Ph.D., associate professor of communication studies, recalls how in February her Communication Studies 100 course — meeting then in the classroom — had been examining public discourse about the coronavirus. A week before spring break marked a distinct shift in that discourse as the virus rapidly advanced.

“Our class discussion grew tense as students shared the ways they understood the coronavirus. Fear crept in. We needed spring break,” Crandall said.

In her “Analyzing Public Texts and Discourse” class, students had been discussing government propaganda and 1950s-era fallout shelters, which the government at that time believed might allow citizens to survive a nuclear bomb blast.

Quickly, discussion turned to the coronavirus.

“Students discussed the fear families (in the 1950s) must have felt as they prepared for possible attack” and how families were growing increasingly concerned about the coronavirus, she said. “What was becoming clear was that all conversations in the academic setting were turning to the virus from every prompt.”

For Crandall, the transition to an online classroom has meant a much different learning community.

“I had a student say his classes are now all homework, completely different. Instead of talking and listening to each other articulate their thoughts in person, students are in their rooms alone with a screen and a keyboard. My students came ‘back’ from spring break to a black-and-white asynchronous discussion board,” she said. “The context shifted, and now the communication skill of writing is suddenly majorly important. The ability to make videos of yourself and upload them is suddenly required. Many students have struggled with motivation in the new online classroom.”

The transition has been difficult for both students and faculty, Crandall observes.

“As a teacher, I have clung to 91勛圖厙’s mission, which states that we expect professional and academic excellence. Yes, everything is different. Yes, we have a range of students with different sets of obstacles to work around and through. And yes, we are capable of thinking and learning and listening and adjusting and striving to be academically and professionally excellent anyway,” she said.

For Crandall, the experience underscores her appreciation for learning communities built in face-to-face classrooms.

“Students file into these physical spaces two to three times a week in all kinds of moods affected by the weather, the pressures of juggling a 15-to-18-credit set of schedules, the volatile nature of young social lives, the anticipation of their extracurricular activities, and often lack of a good night’s sleep,” she said. “Class discussions take off in unanticipated directions as students and faculty focus together on course material. This ephemeral experience is hard to describe and is what makes the in-person learning community so enjoyable and so valuable.”

'Thinking Ahead to Better Times'

Nancy Staub, Ph.D., professor of biology, said that while remote learning is allowing her to shepherd her students through spring semester, it can’t begin to replace the fulfillment she experiences through personal interactions in the classroom.

“I really miss seeing and interacting with my students in class. Though I see them on Zoom, it’s of course not the same,” Staub said.

“What I love about teaching is interacting with students and that has been taken away," she said. "But I’m in the middle of talking to my advisees about fall classes, so we’re enjoying thinking ahead to better times.”

- Academics

- Student Life

- College of Arts & Sciences

- School of Business Administration

- School of Health Sciences

- Academic Vice President

- Undergraduate Admissions

- University Advancement

- Accounting

- Communication Studies

- Biochemistry

- Biology

- Chemistry

- History

- Nursing

- Religious Studies

- News Center