White Space and Slowing Down: Poet giovanni singleton

“I’m really interested in moving more off the page and refashioning what the book can be,” said visiting writer and creative writing professor giovanni singleton during an interview with 91吃瓜网 Magazine in February 2019.

Meagan Ciesla, assistant professor of English and director of the writing concentration, introduced singleton at the start of her presentation with 91吃瓜网’s 2018-19 Visiting Writers Series. “We're always looking for writers who approach their work in a new and innovative way,” Ciesla said in an interview. “[singleton’s] books are a great example of how interdisciplinary a writer’s work can be.”

singleton, who prefers that her name not be capitalized, is the author of published poetry collections “Ascension” (winner of the California Book Award for Poetry) and “AMERICAN LETTERS: works on paper,” and is the founding editor of nocturnes (re)view of the literary arts. She received the 2018 Stephen E. Henderson Award for Outstanding Achievement in Poetry, as well as fellowships from the Squaw Valley Community of Writers, Cave Canem and the Napa Valley Writers Conference.

singleton sat down with student writer Alyssa Cink for a Q&A about her writing inspiration, experimentation with form and life as a poet.

Q&A

Cink: You’ve said Alice Coltrane’s art and music have inspired you. In what ways has her life guided your poetry?

singleton: “I think what Alice Coltrane’s music as well as her spiritual practice did for me was to remind me of the possibilities of being human. She was really good friends with a poet who also meant a lot to me, Lucille Clifton. The two of them are really good friends and they’re both really interested in exploring the expansiveness of being human - not only being connected to a particular identity that may come in the form of which box you check, or what’s written on your birth certificate, but what it means to expand one’s consciousness, what it means to be kind, to be fully engaged in the world around you. That really helped me in my poetry because it meant that I didn’t stop at, say, for example, form, but rather went beyond that to see what’s possible within form and how to explode form.”

Cink: Along the lines of form in your poetry, I read that “Ascension” was recognized for its use of white space, silence and omissions. In what ways do white space and the written word come together in your poetry?

singleton: “I find the notion of white space sort of difficult and complicated because I see it as just space, and it just so happens that the medium that it’s printed on is referred to as being white - in other words, the absence of color. My approach is to just not inject color in the first place. I think that the relationship between space and experimentation is why I’m interested in white space, because often times we’re grappling with how to fix things and tie them down to meaning. I want them to be moveable. Consciousness is always moving. I want that to be reflected in my work. I think that in order to understand the things that do happen, to understand the quatrains, the purpose of rhythm, they hit against other things, which is knowing of space. You can’t know sound if you don’t know silence. They’re interconnected.”

Cink: Your poetry has been described as “minimalist.” Was that intentional? Is this a style or movement you’re drawn to?

singleton: “I am drawn to minimalism, but if I’m honest, one of the things I look at is the fact that I have a lot of jobs. I have to be really efficient when I find a moment to actually write something down … and I’m interested in things we think we understand, and unpacking them… For example, in one of my poems called ‘Caged Bird,’ it centers an image of a bird cage that is made up of repetition of the word ‘bird.’ I’m really interested in unpacking that word and we see it, and it’s these four letters, but what else comes to mind each time it happens?

I’m also somewhat of a failed perfectionist. I feel like we repeat things until we learn something new, a process of accretion - each time it’s mentioned, it takes on a different meaning. For me, it’s a meditation of, 1) calling things into being and then 2) sitting with and trying to get some kind of really intense and meaningful understanding.”

Cink: How old were you when you started to discover and experiment with poetry?

singleton: “Probably when I was in high school. But before that, I was always fascinated. Language to me seemed magical. It started pretty early on, my fascination with letters and making marks. My grandfather used to take me to the local drug store and say, ‘You can have anything you want.’ I always chose something I could make a mark with.”

Cink: Comparing your first poetry collection to your second, how have the writing experiences and themes been different? Or, what did you learn from publishing your debut collection that guided or inspired your second?

singleton: “I know that [both collections] were unintentional. The first obviously was very much connected to encountering Alice Coltrane, meeting her, attending her last concert, going to her ashram, and then her death. It came out of a sort of grief, and at the time I was working as a temp at these law firms in San Francisco, and sort of adrift. I’d not really committed myself to poetry, hadn’t written in 10 years. I set about writing every day as she was transitioning from death and rebirth. That was my practice, my way of dealing with the loss. And at the same time, trying to find a way back and make a decision about whether or not I was going to really commit to this poetry thing. It was really about that process, it wasn’t about making a book.

I was approached by the poet Brenda Hillman who said, ‘Let me just see everything that you have.’ I gave her just a stack of mess that I’d been working on for about 50 days, and it was about the length of a book. So that’s how the first book came into being. But it was really about a search for completion around my connection with the person who I’d been looking for for years, most of the time while I was in graduate school, which was where I first heard of her.

And how it relates to my second book ... since the early ‘90s and since taking graphic design class in graduate school, I had been working on these image-based works. I would do one here and there, it was not anything I was consciously sitting down every single day and attending to. So then a publisher approached me [about a manuscript] and again, ‘No, I just have these random things and they’re mostly image-based. You know, nobody would care about these things.’ He said, ‘Well, send them to me.’

With ‘AMERICAN LETTERS,’ I really wanted to meditate on certain things and how I was starting to see them visually, instead of primarily just text-based. All of this is in hindsight, too, because I don’t think, ‘Oh, I'm going to sit down and arrange this in the shape of a bird cage.’ Also, I had to teach myself. I'm on a serious [learning] curve when it comes to InDesign.”

Cink: As students, sometimes it’s hard for us to define our writing goals. How do you define your goals as a writer? How do you decide what comes next?

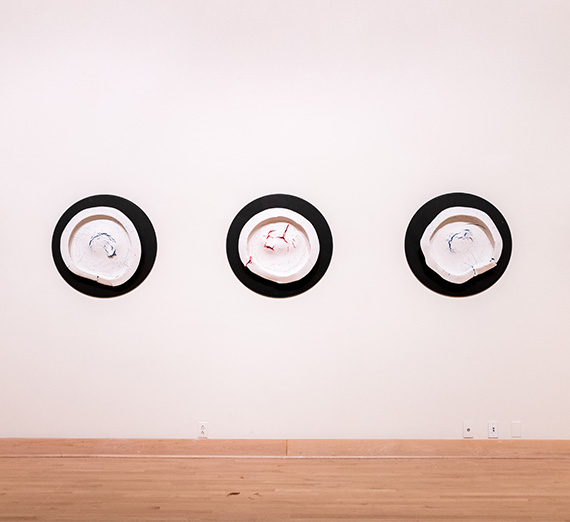

singleton: “I don’t. Honestly, I don’t. I don’t have the anxiety that nothing else will come. I just keep making messes and following my own impulses, and hope that it can be a benefit to others when it comes into the world. I just don’t have that kind of pressure. And I realized that because of the training from graduate school. I stopped writing for 10 years after three intense years of ‘This is what I’m trying to do’ and ‘This is my intention.’ I intend to bring forth what it is that I’m meant to bring forth into the world. Trying to show up for that is the hardest, because you want the prizes, you want the invitations, you maybe even want the books. Right now, I see myself working toward trying to get my things up on the wall in a few exhibitions. I’m really interested in moving more off the page and refashioning what the book can be.”

Cink: That feels like a comforting and also a liberating mindset, that something can emerge just as it is.

singleton: “But I wouldn’t be in this place without that [graduate school background]. I wouldn’t be able to experiment without the tradition, which I continue to be fascinated by. I like that it’s there as a model. It’s really important to get training and then find out where those edges are and how to push past them. I’m as surprised as anyone else might be about the direction my work has gone, and I like that feeling, too. I think that’s what I try to instill in students – how to see things not only new but also to recognize tradition and history and influence."

Cink: What are some of your favorite lessons that you like to share with aspiring, young writers? Any advice or perspectives that young writers might learn from?

singleton: “Across the board, for all of the things I teach on, the one critical thing is that of paying attention and not being in a hurry. You miss a lot when you’re in a hurry, when you just don’t slow down.”