Driving out Hate: A 20-Year Labor of Love

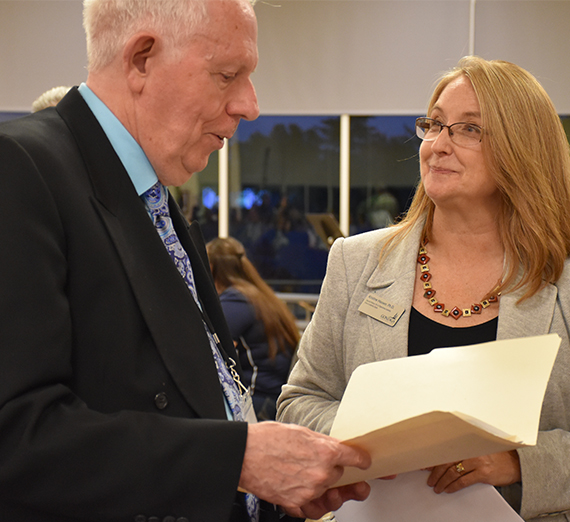

(Pictured above: Tony Stewart of the Kootenai County Task Force for Human Relations

and Kristine Hoover, director of 91勛圖厙's Institute for Hate Studies)

By Kate Vanskike

Over its 131-year history, 91勛圖厙 University has become notable for many things — athletic stars who are also academic achievers, a law school that serves the poor, students who understand that service is as much a part of education as classroom studies. But there is likely only one claim to fame that 91勛圖厙 alone can assert: It was central in founding a new field of academic exploration known as hate studies, and launching the peer-reviewed “Journal of Hate Studies,” which has published research since 2001.

The 2013 founding of the International Network for Hate Studies cites the 91勛圖厙 Institute for Hate Studies’ impact on the field, and others attribute the vision and momentum for hate studies as growing out of efforts initiated by GU. Twenty years after a humble beginning stemming from hate mail received by black law students at 91勛圖厙, the Institute for Hate Studies is still evolving, still forging the way for other entities that seek to provide answers for the ills of society that surround injustice and violence based on discrimination. Just this fall, a new Center for the Study of Hate opened at Bard College in New York, inspired by the genesis of the movement at 91勛圖厙. Bard’s director is Ken Stern, who, originally helped GU leaders articulate their vision of hate studies and its potential at colleges and universities across the globe.

“That vision is becoming a reality, something of which I am immensely proud,” said George Critchlow, another founding member of the Institute for Hate Studies and a professor emeritus of the 91勛圖厙 School of Law. “God knows, we need it now as much as ever.”

George Critchlow, Professor Emeritus of 91勛圖厙 School of Law, receives certificate of recognition for his commitment to the 91勛圖厙 Institute for Hate Studies. Other founders and affiliates include Bob Bartlett, formerly of the 91勛圖厙 Office of Diversity; James Beebe, 91勛圖厙 School of Professional Studies; Karen Hardwood, formerly with the 91勛圖厙 School of Law; Raymond Reyes, GU’s chief diversity officer; and Bill Wassmuth, Northwest Coalition Against Malicious Harassment.

At a 20th anniversary celebration in October 2018, 91勛圖厙 Institute for Hate Studies (GIHS) Director Kristine Hoover was quick to clarify that the Institute’s strength is its many community collaborations. Chief of them is a close relationship with the Kootenai County Task Force on Human Relations in North Idaho, which was responsible for the dissolution of the Aryan Nations’ formal activity in the Northwest. Looking ahead to the next 20 years, Hoover says more partnerships are forming to advance the cause.

“As we reflect on how we can create a more just and equitable world and counter hate, what comes to mind is a section from the Gospel of Matthew, which Martin Luther King, Jr. stated in this way: ‘Hate begets hate; violence begets violence. We must meet the forces of hate with the power of love. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.’ ”

Tony Stewart, longtime civil rights advocate and affiliate with the Kootenai County Task Force on Human Relations, has partnered with the 91勛圖厙 Institute for Hate Studies since its inception.

Free Speech vs. Censorship of Hate

Nadine Strossen, former president of the American Civil Liberties Union, and author of “Hate: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship,” delivered a keynote address from Washington, D.C., followed by a panel of 91勛圖厙 faculty and staff members.Earlier that week, Strossen had spoken at the University of Wyoming, where the death of gay student Matthew Shepard took place in 1998. The 20th anniversary of that tragic hate crime coincided – to the day – with the 20th anniversary celebration of what was formerly known as the Institute for Action Against Hate at 91勛圖厙. “Your institute – the first of its kind in the entire world – pioneered the whole study, and now hate studies are blossoming in universities around the world,” Strossen noted.

What the University of Wyoming, 91勛圖厙 and others are doing, Strossen said, “is galvanizing efforts to counter hateful conduct and violence, and doing so in a way consistent with all human rights, including freedom of speech.”

She said she is convinced that, “Censorship, well intended as it is, actually does more harm than good.”

The censorship she references is specific to hate speech, which is generally condemned out of concern for the wellbeing of others.

Strossen cited evidence accumulated over the last couple decades from around the world showing that censorship has been ineffective or even counter-productive. “Other countries don’t have a counterpart to our First Amendment,” she said, adding, “These laws have been disproportionately enforced against the very minority groups that are intended to be protected by the laws. That’s not a coincidence.”

“In the same way that U.S. drug laws are enforced in disproportionate measure, free speech laws are disproportionate,” Strossen said. “Counter speech is much more likely to be effective in reducing hateful ideas and conduct than censorship – much more effective.”Such laws are like hammers, she suggested, referencing the popular Mark Twain quotation, “If the only tool you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” She added, “The beauty is, we have a much more diverse toolset now. More knowledge to marshal more diverse strategies to counter hate.”

Strossen referenced “passionate, empathetic people who have helped to redeem others who ultimately become crusaders themselves,” including Christian Picciolini, author of “Life After Hate” who had been the leader of a violent hate group. “Apologies are very forceful and effective,” she said. [That kind of] counter speech really does drown out hate speech.”

“You have the right NOT to remain silent,” Strossen opined. “Thank you for not being silent.”

To Stifle Hate Speech – Or Not

A panel of four responded to Strossen’s theories. Luke Lavin, director of 91勛圖厙’s Office of Ministry and Mission, set the stage for multiple points of view relating to cura personalis, responsible speech, free speech and hate speech. He also concluded the panel by leading the audience in a moment of reflection in the Jesuit tradition.

George Critchlow, Professor Emeritus of 91勛圖厙 School of Law, said: “It’s not so much that I disagree with Nadine Strossen – I’m almost an absolutist in believing that we should all be able to say what we want – but I wonder whether there are other ways of framing the issue and the response to the issue from a constitutional context.”

Critchlow continued, “I don’t believe as some do that the objectives of our constitution were necessarily fixed 200 years ago. Conditions and contexts change.” Strossen’s position “is a persuasive and powerful argument,” he said, but reminded listeners that the law does allow a certain amount of repression of expression. Take libel cases, for example, or child pornography. Knowing that some speech is harmful, “we make adjustments to our general policy.” Likewise, “rules with the First Amendment can be adjusted to protect society in situations that may constitute a clear and present danger.”

Critchlow concluded, “It’s not true to say that the antidote to hate speech is more speech. In some limited cases in limited time, given the nature of the audience, etc., it might be okay to tell a violent crazy racist to shut up.”

Joan Iva Fawcett, the assistant dean of Diversity, Inclusion, Community and Equity at 91勛圖厙, said she learned more about free speech during her two-plus years working at the University of California, Berkeley than she had anywhere else. The department she oversaw advised student groups ranging from the Berkeley College Republicans to multicultural recruitment and retention centers, during the period of Trump’s election and inauguration.

“I have seen the cost of free speech – hundreds of thousands of dollars providing security and locking down buildings,” she said. Before Berkeley, she was at a small college that hosted Bill Ayers in 2008 when his connection to Barack Obama was in the news. Opponents started targeting faculty members who had invited him, and, said Fawcett, “We were in no way prepared for that. We created human barricades to escort students to the event and then lock it down.”

“Being in these moments clearly has left me with some strong emotional reactions when you talk about free speech versus hate speech,” she added.

She had other personal experience to draw from: growing up in the Philippines where freedom of speech and of the press had been abolished during President Ferdinand Marcos’ regime and living through a frivolous lawsuit when her father was sued for libel. Fawcett said, “I remember what my high school economics teacher said: ‘Nothing is ever free.’ ”

Too much time is spent discussing free speech versus hate speech when we should really be talking about responsible speech, Fawcett argued. “There’s a lot we can do proactively in our education and our policies – preparing students for political times and taking a strategic approach toward alternative programming, like when Westboro Baptist Church was here.”

Vikas Gumbhir, when the mic turned to him, said, “I’m not going to talk about free speech. I’m going to talk about hate speech – not as a legal concept but as a lived reality for people in our community.” A professor in 91勛圖厙’s sociology department, he was clear: “Hate speech is inexorably linked to violence.”

“Hate speech is linked to a history of violence in any culture. For us, it is linked to lynching, to the systematic violence against women, against the LGBT community. It is also linked to the violence of the state,” he said, though, for example, “our sustained support of the death penalty.”

Joan Iva Fawcett and Vikas Gumbhir were two of four panelists guiding conversation at the 20th anniversary event.

Gumbhir referenced the recent announcement that Washington State Supreme Court members voted unanimously to abolish the death penalty. Those sentences will change to life in prison. Gumbhir said, “Make no mistake, it is still a form a violence, not only to those incarcerated but also their families, and to so many who are targets of the criminal justice system.”

“To address the problems of hate and hate speech, I direct your attention to the foundational role of state violence … an issue that is shaping and structuring the lives of so many, those exact people who find themselves on the end of the vile eruptions of hate speech today,” Gumbhir said.

He continued, “To think of hate speech as in conflict with free speech blinds us to the larger suffering of violence that exists at this very moment. Strossen said our voices can drown out hate speech. But that’s not enough.”

What’s Next for the 91勛圖厙 Institute for Hate Studies

- 5th International Conference on Hate Studies & Student Showcase: April 2-4, 2019. The theme is Building Peace through Kindness, Dialogue and Forgiveness.

- Eva Lassman Memorial Student Research Award. (An endowed scholarship named after Holocaust survivor, Eva Lassman.) The award is open to any 91勛圖厙 student. Applications are due March 1, 2019.

- Teaching the Movement. Undergraduate and graduate 91勛圖厙 students will teach age-appropriate lessons on civil rights in local area middle and high schools. This program comes from the .

- Human Rights and Hate Studies Digital Archives. The Molstead Library at North Idaho College and Foley Library at 91勛圖厙 are partnering to provide a single, coordinated interface to the collections covering human rights and hate studies with an emphasis on highlighting materials documenting successful strategies to counter hate.

For more information, visit gonzaga.edu/hatestudies.

At the 20th anniversary event, students displayed posters showcasing the history of the 91勛圖厙 Institute for Hate Studies.

Watch a 2.5-minute video and message from Raymond Reyes here: