Buen Camino

The Camino de Santiago welcomes pilgrims from around the world to walk in the footsteps of Saint James. Alternatively referred to as the “Way,” the Camino routes are considered among the top three religious pilgrimages for Christians, next to Rome and Jerusalem.

Though many modern-day pilgrims elect to walk for non-religious reasons – physical, emotional or historical – the original intent of the Camino was to prayerfully trace the way of Saint James along the Iberian Peninsula to Santiago, Spain, where his remains lay entombed under the altar. Upon arriving at the Cathedral of Santiago, pilgrims can receive a compostela (a certificate of completion) and attend one of many daily pilgrim’s masses.

The long walk, punctuated by cross-cultural encounters in small towns across Spain, affords pilgrims plenty of time for contemplation and discernment. There are more than two dozen Camino routes with varying lengths and difficulty. Pilgrims elect their route, starting point and the number of miles to complete each day. Overnight accommodations include albergues (similar to a hostel), small hotels, convents and monasteries. The only requirement to receive a compostela is either to walk the final 100 kilometers or bike the final 200 kilometers, and to have stamps in a pilgrim’s passport to prove it.

While each pilgrim’s intent and experience are unique, rarely does a pilgrim complete the Camino unchanged.

“Hey California! How you doing?”

Connie Davis (‘67) walked the last 130 kilometers of the Camino in September 2017. She spread the distance over six nights and seven days, beginning in Sarria and ending in Santiago.

On the first morning of her pilgrimage, Connie was ready to be on the trail at 7 a.m., her headlamp shining in the still-dark streets of Sarria. She met a 65-year-old fellow American who had already been on the trail for five weeks and carried everything on his back. They walked together, swapping stories while he showed her the scallop shell markers to look for on the trail.

At age 28, Connie had climbed to the base camp of Mount Everest. “I knew that I could do anything I wanted to do. There was something inside of me that pushed me.”

After she graduated from 91勛圖厙 in 1967, she went on to medical school where she was one of two African Americans and one of five women in her class. She continued as a physician for many years, traveling around the world to assist in the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

“You have to figure out what you want, and then you figure out how you are going to achieve that,” she said. “The Camino was the same idea. I told myself, ‘You wanted to do this Camino in gratitude that you can still do it.’ Then, my brother said, ‘Forget it!’ He didn’t think I could do it. The gauntlet was cast down. I was going to walk the Camino.”

As Connie continued on the Camino, she met people from around the world—Spain, Italy, Australia, the U.S. She built friendships in the time they shared on the trail and in the towns at night.

One group always greeted her by referencing her home state in the U.S., “Hey California! How you doing?” They remembered each other's names and looked out for one another on the trail in true pilgrim fashion.

For Connie, getting up in the morning was the hardest part, but once on the trail with fellow sojourners, she was content to continue on. She kept the wise words of her first-day companion with her through the journey, “It’s your Camino.”

Connie Davis lives in Mexico. She is currently writing a book about adopting her daughter from Ethiopia.

A long walk with the woman I love

Richard (‘73, ‘80) and Frankie White (‘74, ‘78) held demanding jobs their entire lives. Richard was a successful lawyer and adjunct professor in the law clinic at 91勛圖厙, and Frankie was a teacher and adjunct professor in the School of Professional (now Leadership) Studies. Neither knew how they would handle the rapid change of pace when they retired. Walking the Camino helped ease the transition.

“I was afraid that I might be worried about what was next, that I wouldn’t be able to quiet myself down and be happy with uncertainty,” said Richard, who retired the weekend before beginning the Camino. “I learned that I can be at peace with not knowing what is next. It wasn’t a perfect peacefulness, but, for the most part, I was able to not worry about what the next stage of life would bring.”

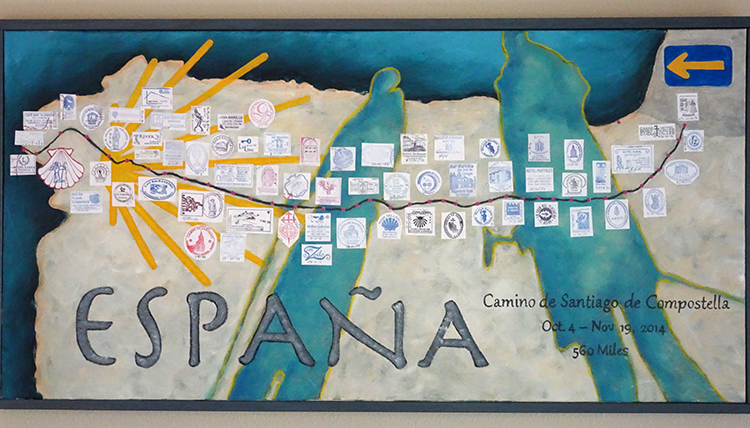

The Whites walked the Camino Frances (French Way) in 2015 with longtime friends and fellow Zags, Vince Herberholt (’73) and Cathy Murray. They planned the trip over two years and read upwards of nine books apiece. On the weekends, the Wrights went on long walks around Spokane, aiming for 12 to 14 miles at a time. They tested backpacks and trekking poles, wore out many pairs of shoes and tried to find the perfect pair of socks.

On the first night of their 560-mile trek, the Whites met and became fast friends with another couple from Oakland, California. The three couples finished the Camino together and continued on after Santiago to Finisterre, known in Camino terms as “the end of the world.”

“We started each morning with gratitude,” Richard said. “We shared how wonderful our lives are and how grateful we are for each other, our children, our grandchildren and our friendships.”

Once out on the trail, each person walked at their own pace, giving each time for silence and prayer. Frankie enjoyed taking pictures, and Richard settled into the repetitive nature of the long walk.

“Of the six-to-eight hours we were walking, I would be surprised if we spent more than two hours talking to each other,” Richard said. “I remember having no sense of time. It was a pleasant surprise when Frankie would say, ‘We’re here.’ She was the navigator. I had one job—to keep an eye on her at all times and to not get lost.”

The Whites visited all of the churches along the Camino, attended Mass and received pilgrims’ blessings. The experience of walking was meditative and spiritual, they said, and it helped them leave the busyness behind for a month and a half. Both experienced a change in the type of conversations they had with God.

“Everyone walks their own Camino,” Frankie said. “It will be uniquely yours. You shouldn’t expect anything out of it, but what you will receive is a tremendous grace from doing it.”

Richard and Frankie charted out pilgrimages for the next four years, including the other two thirds of the 1200-mile Via Francigena, which stretches from Canterbury to Rome. They plan to continue walking pilgrimages as long as their health permits.

“I had an expectation that the Camino would be a life-changing event, that it would redirect our ambitions and be a bridge of sorts between what I was doing and what I was going to do,” Richard said. “I came back and was doing the same thing as before left, but I was more peaceful about it. Don’t expect or desire great revelations. Just be happy on a long walk with the woman you love.”

Richard and Frankie White split their time between Spokane and the Oregon coast. They enjoy long walks in both places in preparation for their next pilgrimage.

A rite of passage

Sam (‘19) and Joe (‘21) Arney walked the Way on separate occasions when they were in high school, each of them with their dad, Bill.

“It was very nice to have uninterrupted whole days together, alone with each of my sons to talk about life,” said Bill.

Neither he nor his sons set out on the Camino as a religious quest. Instead, they focused on the history and the physical ability to complete a journey of this magnitude. For Joe, the Camino invited self-realization and the recognition that it was unusual to see parents and children walking together.

“Joe took to telling people that he talked about sports and his dad talked about life,” Bill said. “He figured out that it was something special to do with his father.”

Sam had a similar experience.

“My dad and I were never close growing up,” Sam said. “Walking the Camino brought us super close. We were sleeping in bunk beds, sharing all of our meals and walking together every day. At the end, he told me he loved me. Spending that time together was really special for me.”

While their quest was not religious in nature, Bill and Sam vividly remember participating in a religious act. They were bundled in their warmest gear braving a snowstorm as they ascended to the Cruz de Ferro (the Iron Cross), one of the highest points on the Camino Frances. The cross rose out of the clouds and they each tossed a rock from home onto the pile of the rocks from previous pilgrims.

“Religion is about linking yourself to the past,” Bill said. “Walking the Camino can be very instructive. It helps you sort out what’s important.”

Bill Arney and his wife, Pam Stewart, live in Friday Harbor, Washington. Sam is a senior at 91勛圖厙 and Joe is a sophomore.

Breaking routine over 655 miles

Henry Widdicombe (‘20) pieced together three different routes of the Camino after his study abroad experience in Florence in the spring of 2018. He had six weeks before his plane departed Europe, and he committed to filling each day with lengthy, strenuous hikes.

“I decided on the Norte and Primitivo [routes] because they are less traveled, more scenic and more difficult,” he said. “There is a Camino saying that, ‘He who goes to Santiago without passing through San Salvador, visits the servant (St. James) but not the master (Jesus).’ The Primitivo is the original historical route followed by King Alphonso II in the 9th century.”

When Henry discovered he was walking too fast and conquering too many miles in a single day, he added a 4-day detour to a Franciscan monastery to see the largest remaining relic of the cross. He walked 45 miles, crossed two mountains and made a last-minute change in accommodations when he found an albergue closed. When he arrived at the monastery, he learned that the relic of the cross left the monastery 10 days prior and was currently on loan to a museum as part of a Jubilee year tour.

“It was important for me to recognize that my life is so oriented around routine—I am a very orderly person and have a firm daily routine,” Henry said. “On the Camino, that developed into a willingness to go with the flow. I realized that each time my plan for the day fell apart, it was never horrible. I was never doomed.”

Not having a routine was the hardest and most rewarding aspect for Henry, he said. He was forced to accept each day as it came and relied on the help of strangers to point him in the right direction.

Henry met Australians, Germans, Italians and fellow Americans on his 655-mile journey through Northern Spain. Sometimes, he walked with the people he met for a couple days. Others he saw time and time again on the trail or in the towns on the way to Santiago. He stayed in albergues and donativos, shared meals with fellow pilgrims, and constantly found himself shedding excess gear from his pack.

“The one thing that was the same every day was walking,” Henry said. “I never once slept in same bed. I was never anywhere for more than 18 hours. I was in a constantly changing environment.”

The long pilgrimage infected Henry with what he called, “the itch” to keep doing things like the Camino, to continue spending time outside, and to being a backpacker for life.

“I’ve always been particularly drawn to the outdoors in a way that is about more than the fact that I like to be outside,” he said. “Outside, not only am I relying on my own strength and intelligence, but I am also experiencing creation as a way of looking at God and seeing God in his creation. It is wonderfully made, and it cemented that feeling in me of a close relationship with God as Creator. It’s very Jesuit.”

Henry and a fellow pilgrim from Nebraska decided to stay in an albergue three miles from Santiago to afford them the opportunity to arrive in the square before anyone else the following morning. They woke up before dawn, walked into town, took pictures with their respective university flags and acquired their credentials. Then, they sat in the square for several hours watching other pilgrims finish their Camino, knowing exactly how they felt.

“It’s intimately intertwined with things I’ve done in the past and with the arc of my life as a whole,” Henry said. “There are things I experienced and graces I received that are in the process of developing and that will be unendingly helpful in my career and relationships in the future. The Camino planted a seed that will continue to grow.”

Henry Widdicombe is a junior at 91勛圖厙, where he is studying philosophy. When he is not studying, he enjoys spending time outside.

Discovering the ‘Why’ of walking the Camino

Bob Strange (‘66) and his wife, Sandy, walked the Camino Frances in 2013, when Bob was 69 years old and did not have any cartilage in his knees. They both had moments of doubt in the early stages of the Camino, but neither decided to quit.

Bob and Sandy settled into the contemplative experience of getting up in the morning, walking for a few hours and listening to their own footsteps over 480 miles. They encouraged each other and enjoyed both the companionship and the solitude that comes from the pilgrimage.

“People have different reasons for walking the Way,” Bob said. “It’s important not to have expectations of what others people journey should look like. All of their reasons were valid.”

Bob started connecting with his spiritual journey in 1976. Walking the Camino helped him integrate all of his beliefs and to see the universe as connected and benevolent. Bob paid special attention to the intention of forgiving his late father and asking his father for forgiveness.

“The Camino winds and weaves its way into your life and goes into places you don’t expect it to,” Bob said. “It helped me focus on the fact that I was more interested in being a good father and husband than having a great career.”

On the second day of the Camino, Bob and Sandy crossed the Pyrenees Mountains in a roaring snowstorm. The Napoleonic Route closed right behind them, and they could barely see the path ahead. They continued in good faith using the footsteps of those who walked in front of them as their guide.

Five weeks later, they braved another snowstorm for 19 kilometers. They descended a mountain and discovered a little bird flying fence post to fence post ahead of them. The bird led them for nearly two hours and led them to a cafe with a fireplace.

For Bob, walking the Camino was symbolic of the mountains and valleys of life. Doing something like it, he said, is well worth it and helps the pilgrim disconnect from their own echo chamber in their mind by being out there in nature.

“The ‘How?’ ‘What?’ ‘Where?’ and ‘When?’ [to walk the Camino] are the easy questions,” Bob said. “Every ‘How?’ needs a great ‘Why?’ If you can figure out why you are walking, everything else falls into place.”

Bob Strange and his wife, Sandy, live in Texas. Once per year, Bob travels to the Rocky Mountains in Colorado with his sons, grandsons and nephews to climb a fourteener.

Walking in memory of their children

George and Jane Starks walked the Camino Frances in 2009 to honor their son, Michael, who died tragically in a fraternity hazing incident in 2008. George, Jane and their son, Georgie Starks (’94), began in Pamplona, Spain. Their son, Jason, daughters, Kelly and Megan, and son-in-law, Ryan joined them in Leon for the final 300 kilometers to Santiago. They hoped the pilgrimage would be a cathartic experience after Michael’s death.

The Starks left a funeral card and pictures of Michael in a church in Melide, Spain, along the Camino. They visited the church—which they now refer to as “Michael’s Church”—on their subsequent caminos in 2011, 2012 and 2014, wherein they found the memorial to their son untouched.

George and Jane completed their second camino from Pamplona to Santiago in 2011, and, in 2014, they walked the full Camino Frances from Saint Jean Pied de Port to Santiago. In 2012, between their two Caminos on the French route, they walked the Camino Primitivo from Oviedo to Santiago. Georgie picked up a bicycle in Madrid and rode alongside them.

Their constant companion, Georgie was a prolific note-taker and greeter on the journey, and, according to his father, epitomized the Camino de Santiago in every sense. As they walked, Georgie talked about his time as a student at 91勛圖厙 in the early 90s, and was quite receptive to travel.

“Georgie was an absolute gem in meeting new people, inviting them into his heart and sharing his life with them,” George said. “That’s who he was.”

A couple weeks into the Camino, George and Georgie looked quite scruff and took to calling each other by their trail names—Ratso (Midnight Cowboy) for Georgie and Che for George.

In September of 2017, Georgie lost his 11-year battle with cancer.

“Every day on the Camino is what we have,” George said. “We take our first step in the morning. We don’t know where we will end up. It’s the same in life. Tomorrow is a promise and yesterday is gone. It is something that is unforgettable.”

George Starks and his wife Jane live in Anacortes, Washington. Their forthcoming caminos will be in honor of their sons, Georgie and Michael Starks.

We had an overwhelming number of responses to our request for Camino stories, and are grateful for all of those who shared their experiences.

- Alumni

- Arts & Culture

- Faith & Mission

- Global Impact

- Division of Mission Integration