The Future of Cars

(Republished from 91łÔąĎÍř Magazine 2017)

As a kid, Rhonda Young didn’t play with Matchbox cars or electric trains.

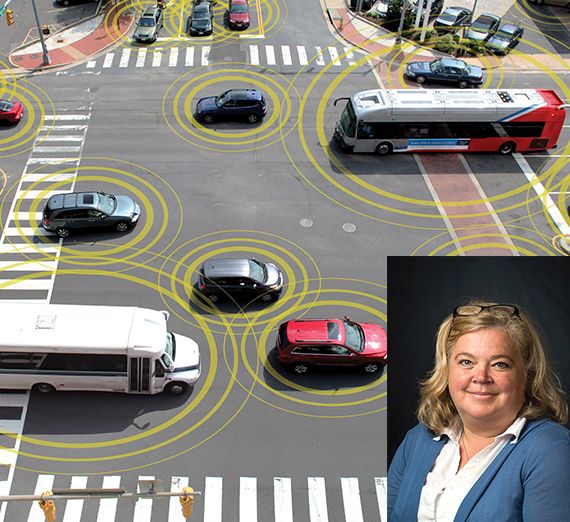

But she did imagine how roadways work, and how transportation moves people to places they need to go. So it comes as no surprise that she is among the nation’s leaders in helping improve transportation engineering education in the country’s colleges and universities. At 91łÔąĎÍř, where she is associate professor of civil engineering, she and students research driverless cars. (Actually, she prefers the less-frightening term “connected vehicles.”) These cars of the not-so-distant future rely on high-tech communication infrastructure that will enhance traffic safety and improve their effectiveness.

“Transportation is something people care about; it affects their daily lives,” says Young, whose work has yielded two major governmental grants. “It’s a great equalizer in that it allows most people to get to their jobs and to their recreation. Transportation has tremendous community impact.”

Connected vehicles gather data and share it with nearby connected vehicles and the communication system via a short-wave frequency up to 1,500 feet.

The idea of driverless cars spurs jokes and legitimate fears alike. It harkens us back to “The Jetsons” cartoons and to the once-improbable gadgets of James Bond. But Young, who has worked extensively in the area of connected vehicles, finds nothing alarming about the notion of getting into a car and having it drive itself while it communicates with adjacent vehicles.

“It would create greater safety,” she says, adding that in 2018, there will be federal rules governing the transmission signals of connected vehicles. Through technology, cars will know where all other nearby connected vehicles are. Down the road, it’s possible that stoplights could be eliminated as a result, because self-driving vehicles will have a programmed destination and assignment to drive through an intersection.

For Young, it’s more about the system than the mode of transportation. “People will make decisions about their modes. We are trying to connect people with where they need to go. There are different stages of life, from young kids to elderly, so having a transportation system that meets the needs of all ages and populations, and that is environmentally friendly, will lead to healthy communities,” she says. “That’s the ultimate goal.”

Here’s an example. During winter white-out conditions along the 402-mile stretch of Interstate 80 in Wyoming, which Young studies, timely vehicle-to-vehicle information is expected to save lives and reduce road closure costs. In one recent 11-month period, the Wyoming Department of Transportation estimated $773 million in losses from crash induced road closures. “Other project benefits may include alleviated traffic congestion, improved transit accessibility, enhanced trip planning and better rural transportation options,” Young says.

91łÔąĎÍř is one of seven universities that will collaborate in a $14 million, five-year U.S. Department of Transportation grant to improve the mobility of people and goods in the Pacific Northwest; and Young is among other researchers participating in the $7 million USDOT-funded connected vehicle project in Wyoming.

In the coming decades, Young believes our roads will host a mix of connected and nonconnected vehicles. She expects society to adapt quickly to driverless cars, similar to the switch to color TVs and smartphones.

The car of the future may not only be safer, but will offer drivers more leisure time, as well. Until that day comes, keep your eyes on the road, your hands at 9 and 3, and your phone tucked away. You can’t pretend to be James Bond just yet.